The Variation of Traumatic Engagement Indicated by Hierarchical Levels of Graphical Realism in Waltz with Bashir and Maus

Trauma and its recollection are major themes in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. In both graphic novels, the authors seek to expose the relation of trauma and its effect on memory repression. This effect is extrapolated in the narrative retelling of each graphic novel’s story as it pertains to what Dori Laub expresses as primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of witnessing (75-76), where the degree of recollective connection to a traumatic event is expressed in graphical realism, or apparent artifactual quality. The hierarchical degree of this quality is represented in both Waltz with Bashir and Maus in several modes, including fantastical imagery, comic-style representation, comic-style photography, and the reproduction of real photography. These modes accord directly to the various levels of traumatic experience of all degrees of witnessing, including the reader’s, and describe the effect of memory repression and recollection as it is gained and lost throughout the narrative process.

The degree of graphical representation that is constant in both Folman and Spiegelman’s graphic novels is the comic format in which the characters are drawn in a consistent style and degree of artistic quality. This degree forms the standard, base level for each book’s connection to trauma and witnessing between the narrative and the reader. This level is described by Dori Laub as the third level of witnessing where “… the process of witnessing is itself being witnessed” (76); the reader experiences the repression and recollection of traumatic memory as it is described narratively; the characters of the novels witness their trauma on first and secondary levels, while the reader witnesses their witnessing from the third. It is from this degree of graphical realism where the remaining degrees stack below and above, representing different levels of repression and recollection, and enables the characters and reader to, according to Laub, “. . . alternate between moving closer and then retreating from the [traumatic] experience” (76). In Folman’s Waltz with Bashir, the baseline degree of graphical realism is characterized by its more realistic style of drawing and its traditional panel and speech bubble layout:

Spiegelman’s Maus uses a similarly standard comic layout, but uses the unrealistic convention of anthropomorphisation and black and white coloration:

Both books utilize a consistency in their graphical style to highlight the separation of traumatic connection and witnessing by creating a standard, or baseline to contrast against the less common levels of graphical representation and their significance.

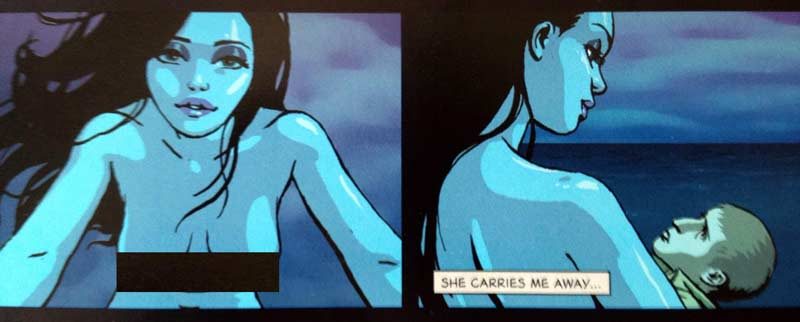

The first level to be explored is the graphical fantasy, which hierarchically, occurs below the baseline level and represents a distancing from trauma. In Waltz with Bashir, this is shown in the retelling of the character Carmi’s fantasy where he dreams of a woman carrying him off of his commando boat:

The depiction of the woman as physically giant to Carmi, dwarfing him and carrying him like a child, contrasts with the realistic art style of the baseline graphics and proves the fantastical quality of the dream’s representation. Carmi states that “I always fall asleep when I’m scared. Even now, I escape into sleep and fantasies” (Folman, 21-22), indicating that the fantastical quality of his dream’s graphical representation aligns with his own understanding of it. Carmi’s escaping from reality by dreaming is similar to the reader’s own escape from the reality of the graphic novel’s subject. The massacre at Sabra and Shatila is set at a distance by the graphical representation of Carmi’s fantasy. A similar distancing occurs in Spiegelman’s Maus, where both the secondary and tertiary levels of witnessing are removed from the novel’s trauma, (in this case, the Holocaust,) when Spiegelman draws a fantastical, perhaps mocking, image of his father as an actor in a movie poster:

Here, Vladek Spiegelman states that “people always told me I looked just like Rudolph Valentino” (13), and Art Spiegelman takes this assertion as an opportunity to distance his secondary witnessing from his father’s retelling of his past. Concurrently, the reader is distanced as a tertiary witness and is removed, albeit temporarily, from the narrative’s recollective goal. In both Maus, and Waltz with Bashir, the graphical effect of distancing is experienced by both the secondary witness, (the narrator), and the tertiary witness (the reader), which affirms Laub’s assertion that trauma is “compelling not only in its reality, but even more so in its flagrant distortion and subversion of reality” (76). By depicting these fantasies, both authors are strengthening the representative power of their narratives by varying the distance in which the reader is engaged with the associated trauma.

This varying of distance also occurs in the higher levels of graphical realism that both novels contain and creates an increasing closeness between the reader and the narrative. Drawn photographs are included in both novels and represent a more direct link to the trauma of each’s narrative’s event. These photos exist at a higher order of realism in comparison to the baseline and fantasy graphical styles. In Maus II, drawn photographs of family members are shown, accompanied by descriptions of each person’s fate according to Vladek:

Here, the drawn photographs are included in baseline comic narrative and superimposed upon it, signifying their higher order of graphical magnitude and their existence as true narrative artifacts. Vladek states that “ here it’s their two kids, Lolek and Lonia, what stayed by us, in Sosnowiec, in the war… the little girl, she finished with Richieu in the ghetto” (114). This depiction and description of the drawn photos creates an instance of trauma recollection that is experienced similarly by both Art Spiegelman and the reader; the drawn photos allow both Art and the reader to share the same role as secondary witness. This shared role is also described in Waltz with Bashir where Ari is told about a war photographer who eventually lost his state of dissociation:

Like in Maus, the drawn photos are depicted as on top of the comic’s panels, as superimposed elements, but unlike in Maus, they are not expressed as real artifacts in the baseline graphical narrative. They are instead either the representation of Ari’s imagination, or included as outside evidence for the reader. In either case, the witnessing of the drawn photos and the description of their origin are secondary experiences to the traumatic event for both the reader and Ari. In describing the story of the war photographer, the Professor states that he “kept thinking he was seeing [the traumatic events] through the lens of an imaginary camera” (58), not unlike the experience of the reader and the graphic novel itself. However, by including the drawn photos, the baseline graphical narrative is supplemented with a level of secondary witnessing, allowing the reader to briefly rise above the tertiary level of the baseline narrative and gain closer insight to the novel’s described trauma.

The power of raising the reader to a higher level of witnessing is realized again by the inclusion in both novels of real photographs. Because these photographs are not drawn, they represent evidence of the each narrative’s events at a the highest level attainable in the graphic novel medium. In Maus, a photograph of Vladek in his camp uniform is shown in the baseline narrative and superimposed for the reader as a real photograph:

Artie is drawn holding the photo and stating “Incredible!” (135). By including Artie’s reaction to the comic representation of the photo and showing the real photo, superimposed, the reader is once again brought into a shared, secondary level of witnessing. (It is assumed that the reader will share a similar sense of shock at seeing what Vladek truly looked like.) This shared experience is not mimicked in Waltz with Bashir, where at the end of the novel, photographs of slain Palestinians are shown:

Because these photographs are not depicted in comic form, the experience of viewing them is obviously not shared between the reader and Ari. The photos instead acts as a bridge between Ari’s first level of witnessing the massacre, and the secondary level of witnessing offered to the reader. Ari is a first level witness of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, and, hopefully, the reader is not. While this dissimilarity between the novels exists, both utilize real photographs to attain a higher witness level in the reader.

Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir and Art Spiegelman’s Maus both narrativize the act of trauma recollection by including multiple levels of witnessing. The reader is lunged back and forth between tertiary and secondary levels as the primary characters of each work explore memories of the Holocaust and the 1982 Lebanon War. By including varying levels of graphical quality and artifactual evidence, each graphic novel attains a discernible depth that aligns with Dori Laub’s ternary levels of witnessing. By engaging all three levels, both works succeed in shedding light on the intricacies of recollection and the role of the reader. By allowing the reader to witness these traumas at two levels, Folman and Spiegelman have defeated the potential passivity of their medium and created an experience that draws the reader into the severity of their respective subjects.

Works Cited

Felman, Shoshana, and Dori Laub. Testimony Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2013. 75-92. Print.

Folman, Ari, and David Polonsky. Waltz with Bashir: A Lebanon War Story. New York: Metropolitan, 2008. Print.

Spiegelman, Art, Louise Fili, and Art Spiegelman. MAUS: A Survivor’s Tale, II: And Here My Troubles Began. New York: Pantheon, 1991. Print.

Spiegelman, Art. MAUS: A Survivor’s Tale, I: My Father Bleeds History. New York: Pantheon, 1986. Print.